|

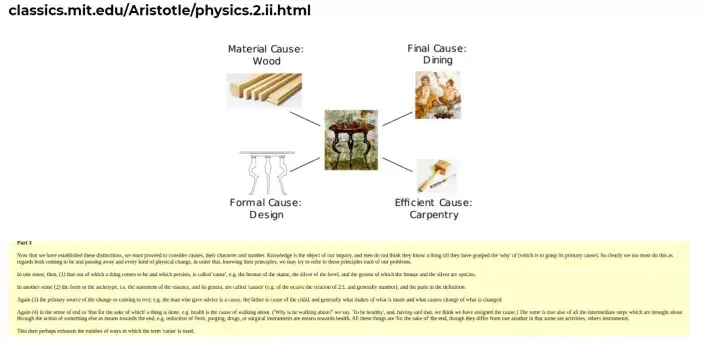

Housing Market Blog At the risk of Re-iterating myself. This Blog looks at the terms of the doamin related to this debaate which ignores Finance, the transfer of home purchase funding from Building societies to Banks and the transfer function represented by money creation and financialisation. Volume 825: debated on Thursday 17 November 2022 That this House takes note of the multiple problems affecting all tenures in the housing market in England; and the case for a coherent strategy to encompass the social, economic, and environmental aspects of housing and construction. Baroness Warwick of Undercliffe Opening the Debate on the above motion. Looking at affordability, the latest ONS figures show that the average UK house price was £296,000 in August 2022, up 14.3% over the previous year in England. Prices in England have gone up by 76% since 2012. Despite regional differences, all areas have experienced increased prices. Average house prices in London, despite it having the lowest annual house price growth rate, remain the most expensive of any region in the UK. The ONS also estimates that full-time employees can typically expect to spend around 9.1 times their workplace-based annual earnings on purchasing a home in England, compared to 3.5 times in 1997. The number of new social rented homes has fallen by over 80% since 2010. The Government committed in their 2019 manifesto to build 300,000 new homes annually by the mid-2020s. I hope the Minister will tell the House what plans are in place to deliver on those numbers, given the stark facts I have listed. We currently face a grave affordable housing crisis which continues to worsen, with 4.2 million people currently in need of social housing in England. Understanding the scale and types of housing need across the country is essential for planning effective policy responses and informing the debate around the need for new homes. People in Housing Need, a report published by the National Housing Federation last December, found that half a million more families are in need of social housing than are recorded on official housing waiting lists. Two million children in England—one in every five—are living in overcrowded, unaffordable or unsuitable homes. Some 1.3 million of these children are in need of social housing, as this is the only suitable and affordable type of home for their families. Need for social housing has risen in all parts of the country, yet the supply of social rented housing has fallen, as I have said, by 85% since 2010-11, with the number of social rent homes available for letting each year also falling since 2014-15. We are living through a severe crisis of housing supply and affordability, which is increasing housing vulnerability. Long-term investment in social housing would provide people with suitable homes that they can afford and support the Government’s commitment to level up disadvantaged communities across the country. Social housing brings down the housing benefit bill, supports better health and well-being outcomes and reduces reliance on temporary accommodation. Last year, housing associations built more than 38,000 new homes. Building these homes directly added £2.1 billion to the national economy, supporting more than 36,000 jobs. Housing associations in England currently provide 2.8 million homes for 6 million people, housing 11% of the population. The lower rents they charge save tenants £9 billion annually, making significant savings for the Treasury by bringing down the housing benefit bill. However, current inflationary pressures are having a significant impact on housing associations’ ability to deliver new developments. According to data commissioned from the Centre for Economics and Business Research, material costs for repairs and maintenance have increased by 14% and it is 12.3% more expensive to build new homes than it was last year. Although Section 106 is not perfect, it delivers significant numbers of affordable homes; currently around 50% of all new affordable housing is delivered in this way. As it stands in the Bill, the infrastructure levy would enable local authorities to divert developer contributions away from affordable housing and towards other unspecified forms of infrastructure. Around two-thirds of Section 106 proceeds currently go towards affordable housing, so this would represent a dramatic tilt away from affordable housing delivery when demand for it is increasing all over the country. It is vital that the energy efficiencies of homes are greatly improved. Over 60% of social homes are certified EPC C or above, but other tenures average just under 40%. An immediate commitment to long-term retrofit funding will do wonders to move people away from gas and prevent residents moving into fuel poverty. Will the Minister protect the existing social housing decarbonisation fund? Can she tell the House when the Government will release the remainder of the £3.8 billion investment up to 2030? Currently, 23% of privately rented homes are non-decent, rising to 29% of homes privately rented by people receiving housing support. Some 16% of owner-occupied homes and 12% of social housing homes are currently non-decent. The recent appalling case in Lancashire reinforces this point. Reform in the sector is often piecemeal and disjointed, as illustrated by the fact that we have had five different Housing Ministers in the past year and 14 different Ministers since 2010. Affordable housing is a key driver of economic growth. Managing and maintaining housing associations’ existing homes directly adds £11 billion to the national economy annually. Housing associations are an essential part of the housing market. Lord Lilley given that the rate of births is below the rate of deaths. We are not creating more households domestically to create this demand for housing. Until recently, the main driver of demand for housing was that households were becoming smaller. As people left home earlier or lived longer after their children had left home, so that there were only two instead of four in the household, or after their partner had died, so that there was only one instead of two, average household size was coming down. This was also aggravated by the sad break-up of families through divorce or separation. That used to mean we had to add 0.5% to the housing stock every year to cope with smaller households. That has come to an end. Young people are now unable to leave home and are leaving later. In 1999, 2.4 million adults aged between 20 and 34 lived at home with their parents. By 2019, 3.5 million people in that age group lived at home with their parents. So what is the reason? The main reason, which I suspect no one else in this debate will mention, is not migration into the south of England or London from the rest of the United Kingdom. That is often the reason given, but in the last two or three decades there has been a net outflow from London and south-east England to the rest of the UK. The inflow is from abroad. We have seen mass immigration into this country on a scale never before seen in our history. We know that the official figures from the last decade understate the numbers coming here. We found, when we asked European residents to register, that there were 2 million more of them than we knew about. Over the last decade, the official figures show a net increase to our population of 2 million from those coming to settle here from abroad. That is equivalent to our having to build cities the size of Nottingham, Derby, Leicester, Middlesbrough, Carlisle, Oxford, Exeter, Portsmouth and Southampton, every decade, just to keep up with the net inflow from abroad. if we allow a continued net inflow of 200,000 or 300,000 into this country, we have to build extra houses on top of the demand of the domestic population that is already here. We can strive to reduce the inflow, but we will still have to build a lot of houses and there will still be a lot of objections to that housebuilding. I do not mind which side of the debate people take, as long as they are honest about it. If they say, “We want to see mass immigration into this country and we are prepared to build all those extra properties every year—the equivalent of all those cities every decade”, that is fair enough, but they may oppose that. Contributions for Baroness Taylor of Stevenage. Between 1945 and 1980, local authorities and housing associations built 4.4 million social homes—more than 126,000 a year—but by 1983, that supply had halved to just over 44,000 a year. This followed a major shift in social housing policy, particularly, but not exclusively, the right-to-buy scheme of Margaret Thatcher’s Government. Failure to replace the stock bought under right to buy means that, in Stevenage, our stock has fallen from 32,000 to less than 8,000 homes. The promise to our pioneers that their children, grandchildren and parents would be housed has been broken. The retained right-to-buy funding regime permits only 40% of the cost of constructing a replacement dwelling to come from right-to-buy receipts. Failing to take account of rising property, land and commodity prices in the construction industry, the shortfall on a new-build property in my area is currently £186,000, forcing us to use additional borrowing, with a trade-off between repairs and management of existing stock or building private homes for sale simply to fund any replacement homes at all. Over 2 million sales of social homes have taken place, but research shows that over 40% of these are now rented privately. Affordable social housing turned into unaffordable private rented housing, with a consequent catastrophic effect on family budgets. It is also economically illiterate, as housing benefit spending has risen by 50%, peaking at £24.3 billion in the last year of recorded statistics. The average monthly rent for a two-bedroom privately rented property in my town is now £312 a week, against the local housing allowance of £195. No wonder there is a cost of living crisis. Against a target of 300,000 homes a year, we are currently building a little over 100,000. This problem will not get better unless we turbo-charge the number of homes of all tenures, particularly social housing, that we build in this country. Let us get back to those first principles of our new towns—of building communities and homes, not just places and houses. Let us take the design and detail of our development seriously and, to meet the challenge we have that Lord Silkin did not, let us build sustainably, so that we do not exacerbate the backlog of £204 million that I will need to decarbonise 8,000 social homes in Stevenage. Lord Best Dramatically fewer people have been able to get on the housing ladder, with owner-occupation for those aged under 30 falling from 47% 20 years ago to under 25% today. Now those wanting to buy face even greater problems, made worse by the hike in interest rates following the fateful mini-Budget. Over 1.5 million households are queuing for social housing from councils or housing associations, but that sector has halved in size, from one-third of the nation’s homes to just 17%, while social landlords face a mountain of extra building and borrowing costs that will hold back their new-build affordable housing programme. For more and more people, the only option is the private rented sector, which has doubled in size during the first two decades of this century. However, here we are seeing falling numbers of available lettings because landlords, deterred by higher interest rates on top of other disincentives, are exiting the market or, in some areas, switching to Airbnb and very short-term lettings. Demand is up by 20% while supply is down 9%, as noted by the noble Baroness, Lady Thornhill. With consequent fierce competition for privately rented properties, young people are spending half their income on securing a rented, not always decent, flat. There are a dozen urgent measures that could and should provide temporary relief, but we also need to address the underlying cause of this national failure. What would make the biggest difference to getting more homes built—as the noble Lord, Lord Lilley, suggests we need to do—and galvanising the process of reducing the disastrous housing shortages? Top of my wish list for fundamental change is the adoption of the mechanisms for land value capture advocated by Sir Oliver Letwin in his 2018 review. Sir Oliver got to the heart of why we have been failing, year after year, to build what we need. Yes, we should resource our local planning departments to speed up the planning process, but that is not why we get such a slow build-out of new developments and build so few new homes affordable to the half of the population on average incomes or less, or why we have developments that continuously fail us on so many counts. We also see SME builders being excluded, despite those firms often being more in tune with local needs, the local vernacular and the local labour market. The housebuilders’ business model requires them to fight, with their lawyers and consultants, for the minimum number of affordable homes—the maximum number of properties they can squeeze on to a site, with the least green infrastructure and the fewest amenities, and to build at a speed that ensures the continuing scarcity that drives up prices. Our system rewards the very actions by housebuilders most at odds with the public interest. Instead, the Letwin review tells us we should take back control. Letwin puts the scale at 1,500 homes but his formula is just as applicable for 150: for every major development, land should be acquired at a price that relates to its current use—for example, for agricultural land, Letwin suggests paying no more than 10 times the agricultural value—with a master plan that determines what is built and parcels out sites to different builders and providers, for a range of uses and tenures. Having bought the land at a reasonable price, using compulsory purchase powers if necessary, a development becomes viable that actually and promptly delivers the social benefits missing today. To achieve this upending of the current, highly unsatisfactory process, Letwin proposes local authorities establish arm’s-length development corporations, as is quite possible under existing law. These would borrow the finance to buy the site and capture the land value uplift. The development corporation’s master plan can then incorporate all the features of healthy place-making. Lord Crisp However, I was surprised to discover, when I talked to the chief executive of one of the major housing developers, which produces very high-quality houses, about regulation—which obviously he did not particularly want—the point he made was that there is nobody who checks up on the regulation. This, I guess, must be known well to other people in the Chamber, but the surprising point that he was making is that there is a lot of regulation but not very much in the way of inspection. Local authorities and others have lost a lot of the staff who would otherwise be making sure that regulation was properly applied. The implication he left me with was that good developers of course pay attention to the regulations, but many others do not. So there seem to be some major problems in the way regulation is handled at the moment. What are the levers that this Government are going to use, perhaps including regulation but maybe including codes of good practice or incentives? How will they ensure that in future we will not see more poor-quality homes being built? Because we are seeing poor-quality homes being built, partly through permitted development rights but also through other routes. How can the Government ensure that we stop the problem getting worse, let alone move forward to improve things? Viscount Hanworth (Labour) 17:02:33 Social housing in the form of council houses and flats had been steadily increasing since the 1920s. The expansion was at the expense of private renting, which often involved severely substandard dwellings. Since 1980, social housing has experienced a radical decline in consequence of the sale of the council properties and the cessation of council house building. Since 1990, the proportion of private renters has increased from a mere 12% to the present 20%, and we have heard much about the pathologies of the sector. In consequence of the failure to build sufficient numbers of houses, there is now a crisis and the shortage has led to inflated property prices. When these are affected by the current high rates of interest on mortgages, the impact on personal finances becomes severe. Lord Khan of Burnley Access to housing is increasingly difficult, especially for those who have traditionally benefited from social homes. There are now 1.4 million fewer households in social housing than there were in 1980, despite the population of our country growing by over 10 million in the same period. Building good-quality and well-regulated social housing is the relief that the Government can provide to so many millions of families struggling today. According to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, over half of renters on low incomes would be lifted out of housing unaffordability were they to be offered homes at social rent levels. We must also look to new and innovative forms of community and co-operative housing, learning from successful models in places such as Sunderland, Liverpool and Lancaster, where they build community wealth or collective ownership and have seen over 25,000 houses built so far. Such models give residents a greater say over design and management and can be paired with new community land trusts to provide community-owned affordable homes. I recognise that home ownership is an ambition for millions and an achievement for many more. In the more immediate term, we need to address the present mortgage crisis, which means that a household refinancing a two-year fixed mortgage will be paying £500 more per month on average. The result of this crisis will be that people who have worked and saved to own a place of their own will lose the roof over their head. Needless to say, on home ownership the limit of ambition should stretch far beyond addressing the immediate crisis—we must ask why home ownership rates have fallen and the number of new affordable homes available to buy has plummeted. Following the Chancellor’s mini-Budget, more than 40% of available mortgages were withdrawn from the market, and lenders priced in interest rates for two-year fixed-rate products at over 6%, and, unfortunately, the Statement today did not address the issues for many people. This has a very real and immediate impact. Mortgage repossessions soared by 91% compared with the same period last year, while the number of orders to seize property are up by 103%. While the situation now is worse than ever in recent memory, this is the latest culmination of a trajectory which began in 2010. There are now 800,000 fewer householders under 45 who own their home and nearly 1 million more people in private rented properties than 12 years ago. For a significant part of the population, private renting will be the right option, but there should be an alternative. The Government’s own White Paper admits that the private rented sector “offers the most expensive, least secure, and lowest quality housing to 4.4 million households”, and they are correct. One-fifth of private tenants in England are now spending a third of their income on housing that is non-decent. https://webbrain.com/brainpage/brain/98FC8BC2-D290-31A1-0868-3987279717D8#-136 #96: The Housing Supply Myth – Cameron Murray & Ian Mulheirn The Housing Supply Myth – Cameron Murray & Ian Mulheirn https://josephnoelwalker.com/96-the-housing-supply-myth-cameron-murray-ian-mulheirn/ @52.18. "The 5th thing is the misunderstanding that there are two markets here. You have two markets, Two prices The Market for housing services is the Rental Market The Market for housing assets is the House Price Just Like Cameron's example of the I Phone price versus the Apple Share Price. These are different markets with different prices and people just don't get that!" Ian Mulheirn. See , Dr Adrian Wrigley. The Principles of Tax Policy 2010 "6. Legitimate government spending generally provides infrastructure, services and welfare payments to resident people and businesses. To benefit from this government spending, a person must own or rent a home or operate a business in the area. The monthly amount people pay to occupy their homes is set in the marketplace, based upon location and the value of natural, commercial and government amenities provided. Landlords charge monthly for these location amenities while home sellers charge a lump sum." "The dominant cause of the collapse in home ownership appears to lie in the mortgage market.66 The overwhelming majority of FTBs need mortgage finance to buy a house. If high prices were weighing on their ability to access finance in the run up to the crisis, we might expect to see the number of new FTB mortgages drifting downwards in the years up to 2007. There is some evidence of this in the early 2000s, but in the five years up to 2007, UK-wide issuance of FTB mortgages was reasonably constant at around 370,000 per year.67 In 2008 that number suddenly almost halved, to 192,000, and didn’t much recover for the next five years (see Fig. 18). Only in 2017 did it regain something close to precrisis levels." Ian Mulheirn. Tackling the UK housing crisis: is supply the answer?2019 Edit The Redfern Review: A grown-up take on the housing crisisNov 16, 2016 1:50 PMEarlier this year, Labour commissioned the chief executive of the country's biggest house builder to lead a study of the decline in home ownership - the main reason politicians are worried about housing these days. The Redfern Review has been published today. It shouldn't be a great surprise that its conclusions don't fit completely with our views - there's very little comment on the needs of private renters - but it does make an important contribution to the debate, and there's a lot we can agree on. Indeed, it takes a more objective approach than parties and industry players have done when they've tackled the same subject - there's refreshingly little dogma or evidence of Taylor Wimpey's commercial interests at play (though it plays down builders' profit-driven reluctance to build enough homes). The report looks at the decline of home ownership between 2002 and 2014, and controversially places more of the blame on restrictions on mortgages post-crash than the increase in house prices. The authors point out that rising house prices did cause the fall in first time buyers in the mid-noughties, but after the crash, when 90% and 95% mortgages were withdrawn, fewer people could benefit from the slump in house prices so home ownership continued to drop. https://www.generationrent.org/the_redfern_review_a_grown_up_take_on_the_housing_crisis The Australian housing supply mythCameron Murray (ckmurray@gmail.com) No r925z, OSF Preprints from Center for Open Science Abstract: Australia’s expensive housing market is claimed to be primarily the result of a shortage of supply due to town planning constraints, leading to political pressure on councils and state governments to remove planning regulations, regardless of their planning merit. We argue that this supply story is a myth and provide evidence against three key elements of the myth. First, there has been a surplus of dwellings constructed compared to population demand, rather than a shortage. Second, planning approvals typically far exceed dwelling construction, implying that more approvals or changes to planning controls on the density and location of development cannot accelerate the rate of new housing supply. Third, large increases in the rate of housing supply would have small price effects relative to other factors, like interest rates, and come with the opportunity cost of forgone alternative economic activities. Indeed, if the story were true, then property developers would be foolishly lobbying for policy changes that reduce the price of their product and the value of the balance sheets, which mostly comprise undeveloped land. Date: 2019-11-25 Mulheirn , Where did all the wealth Come form

Where did all that wealth come from?And what should we do about it?Household wealth in the UK has increased by almost £10 trillion in the past 25 years, from just £4.9 trillion in 1995 to £14.6 trillion by 2017 (all in 2017 money). This is a staggering explosion of wealth. No wonder that at a time when the public finances are under pressure, as they have been since the financial crisis, political interest has grown in the idea of a wealth tax — an annual levy on the value of a person’s wealth. But where did these riches come from and does that shed any light on whether or how they might be taxed?

#Home@ix #Moduloft, The Affordable Housing Manufacturers. Defining the Terms of and Boundary Conditions of our Domain.

The outstanding value of all residential mortgage loans was £1,527.3 billion at the end of 2020 Q3

two thirds of households own the house they live in; half of these are still paying off their mortgage 28,536,000 Dwellings 29,180,071,800 sq ft 29 Billion Sqft . See the At the risk of reiterating myself blog at Realrld.com or homeatix.net Home@ix understanding affordable housing Money into Property, Mortgage Debt and Money Supply Symbiosis. The Dismal Science fails society over and over again. Monday, 18 May 2015MeltFund mortgage total market sizeFor the benefit of our Clients and Partners, here is the total market size of MeltFund. Sources of this data can be found in the notes below [1]. Do not worry yourselves with scientific precision. Observe with care and see the general numbers are large enough already.

= UK £14 BillionFor the United States, multiply by ~6= US $84 Billion For the world, multiply by ~20 = US $280 Billion Here are some more alarming UK numbers. Deny them at your peril:

#Moduloft, The Affordable Housing Manufacturers. Defining the Terms of and Boundary Conditions of our Domain. https://notthegrubstreetjournal.com/2020/12/13/moduloft-the-affordable-housing-manufacturers-defining-the-terms-of-and-boundary-conditions-of-our-domain/

The outstanding value of all residential mortgage loans was £1,527.3 billion at the end of 2020 Q3 two thirds of households own the house they live in; half of these are still paying off their mortgage 28,536,000 Dwellings 29,180,071,800 sq ft 29 Billion Sqft .  The effectiveness of any Model is determined by a number of factors, Integrity of the data, and what scientist/modelers call defining the extent of the models domain, what we might call Parameters or Boundary conditions. To understand "The Housing Market" and make contributions to it a good place to start is How Big is it and what are its constituent parts. What is it. The effectiveness of any Model is determined by a number of factors, Integrity of the data, and what scientist/modelers call defining the extent of the models domain, what we might call Parameters or Boundary conditions. To understand "The Housing Market" and make contributions to it a good place to start is How Big is it and what are its constituent parts. What is it.  What is the housing market? When people buy or sell houses, either to live in or as an investment, we refer to this as the housing market. A house is the most valuable thing many people will ever own. In Britain, two thirds of households own the house they live in; half of these are still paying off their mortgage. The remaining third of households are renters, split fairly equally between private and social renting.( Source. Bank of England. ) How Big is It Physically. What is the housing market? When people buy or sell houses, either to live in or as an investment, we refer to this as the housing market. A house is the most valuable thing many people will ever own. In Britain, two thirds of households own the house they live in; half of these are still paying off their mortgage. The remaining third of households are renters, split fairly equally between private and social renting.( Source. Bank of England. ) How Big is It Physically.  (Source: Building Research Establishment.) From the above table of 2017 Data In the United Kingdom there were 28,536,000 Dwellings with an average Dwelling size of 95SQM or 2,710,920,000 sqm or Errors pp 56/57 28,536,000 dewellings x 95sqm= 2,710,920,000 Sqm 29,180,071,800 sq ft 29 Billion Sqft UK Housing Stock Total (Source: Building Research Establishment.) From the above table of 2017 Data In the United Kingdom there were 28,536,000 Dwellings with an average Dwelling size of 95SQM or 2,710,920,000 sqm or Errors pp 56/57 28,536,000 dewellings x 95sqm= 2,710,920,000 Sqm 29,180,071,800 sq ft 29 Billion Sqft UK Housing Stock Total

29,180,071,800 sq ft 29 Billion Sqft .Plot Size and Dwelling Size   How do we Value it? How do we Value it?  Median House Price to Income Ratios. From Fixing our Broken Housing Market 2017, Sajid David.( Ex Deutsche Bank) Median House Price to Income Ratios. From Fixing our Broken Housing Market 2017, Sajid David.( Ex Deutsche Bank)  The FCA and the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) both have responsibility for the regulation of mortgage lenders and administrators. We jointly publish the mortgage lending statistics every quarter. Since the beginning of 2007, around 340 regulated mortgage lenders and administrators have been required to submit a Mortgage Lending and Administration Return (MLAR) each quarter, providing data on their mortgage lending activities. Key findings The outstanding value of all residential mortgage loans was £1,527.3 billion at the end of 2020, 2.9% higher than a year earlier (Table A). The value of gross mortgage advances in 2020 Q3 was £62.5 billion, 14.7% lower than in 2019 Q3 (Table A and Chart 1). The value of new mortgage commitments (lending agreed to be advanced in the coming months) was 6.8% higher than a year earlier, at £78.9 billion and the highest level since 2007 Q3 (Table A and Chart 1). The share of gross advances with interest rates less than 2% above Bank Rate was 74.2% in 2020 Q3, 10.0 percentage points (pp) lower than a year ago (Chart 2). See the Bank’s data on Effective Interest Rates. The share of mortgages advanced in 2020 Q3 with loan to value (LTV) ratios exceeding 90% was 3.5%, 2.4pp lower than a year earlier (Chart 3). The share of gross advances for remortgages for owner occupation was 25%, a decrease of 3pp since 2019 Q3. The share for house purchase for owner occupation was 55.8%, up 2.6pp from 2019 Q3. (Chart 5). The value of outstanding balances with some arrears fell by 1.2% over the quarter to £13.8 billion, and now accounts for 0.90% of outstanding mortgage balances (Chart 6). The FCA and the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) both have responsibility for the regulation of mortgage lenders and administrators. We jointly publish the mortgage lending statistics every quarter. Since the beginning of 2007, around 340 regulated mortgage lenders and administrators have been required to submit a Mortgage Lending and Administration Return (MLAR) each quarter, providing data on their mortgage lending activities. Key findings The outstanding value of all residential mortgage loans was £1,527.3 billion at the end of 2020, 2.9% higher than a year earlier (Table A). The value of gross mortgage advances in 2020 Q3 was £62.5 billion, 14.7% lower than in 2019 Q3 (Table A and Chart 1). The value of new mortgage commitments (lending agreed to be advanced in the coming months) was 6.8% higher than a year earlier, at £78.9 billion and the highest level since 2007 Q3 (Table A and Chart 1). The share of gross advances with interest rates less than 2% above Bank Rate was 74.2% in 2020 Q3, 10.0 percentage points (pp) lower than a year ago (Chart 2). See the Bank’s data on Effective Interest Rates. The share of mortgages advanced in 2020 Q3 with loan to value (LTV) ratios exceeding 90% was 3.5%, 2.4pp lower than a year earlier (Chart 3). The share of gross advances for remortgages for owner occupation was 25%, a decrease of 3pp since 2019 Q3. The share for house purchase for owner occupation was 55.8%, up 2.6pp from 2019 Q3. (Chart 5). The value of outstanding balances with some arrears fell by 1.2% over the quarter to £13.8 billion, and now accounts for 0.90% of outstanding mortgage balances (Chart 6).  2017-2018 2017-2018  2014 2014  2013- 2013-  https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2020/01/An-outstanding-balance.pdf https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2020/01/An-outstanding-balance.pdf   How are these Lending Decisions Made, and where does the Money Come from? How are these Lending Decisions Made, and where does the Money Come from?  https://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/materials/working_papers/paper499.pdf https://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/materials/working_papers/paper499.pdf

A second innovation is the theory-justified use of an estimate of the proportion of mortgages in negative equity, based on an average debt to equity ratio, as one of the key drivers of possessions and arrears. Possessions and arrears are driven by three economic fundamentals: the debt service ratio; the proxy for the proportion of mortgages in negative equity, calibrated from an average debt to equity ratio; and the unemployment rate. Modelling the three equations as a system with common lending quality and policy shifts helps greatly in the identifying the unobservables. By sharp contrast with earlier UK literature, there is no significant effect on the rate of possessions from either measure of arrears. This important finding is discussed further below. The long-run effects24 on the possessions rate are shown in Figure 7 for the debt-service ratio, estimated proportion in negative equity and the unemployment rate. Figure 8 shows the longrun impact of loan quality and forbearance policy, discussed further below. The figures suggest that in the first possessions crisis in 1989-93, the initial rise in possessions was driven mainly by the rise in the debt-service ratio, combined with lower loan quality, but later the rising incidence of negative equity emerged as an important driver. The persistence of negative equity prevented a faster decline in possessions, despite lower interest rates and the forbearance policy introduced at the end of 1991. In the second possessions crisis, the rise in possessions from its low level in 2004 again was caused by a growing debt-service ratio, and later the increasing incidence of negative equity, which rose sharply in 2008-9. To illustrate the magnitudes implied by this research, a 10 percent increase in the debt-service ratio, for example due to the mortgage interest rate rising from 4 percent to 4.4 percent, is estimated eventually to raise the possessions rate by around 19 percent, and the 6 month arrears rate, corrected for measurement bias, by 15 percent. This calculation holds the proportion of mortgages in negative equity and the unemployment rate fixed. At 2009Q3 house price and debt levels, a fall in house prices of 1.4 percent would raise the proportion of mortgages with negative equity from an estimated 8.5 percent to 9.35 percent, a 10 percent proportionate increase. An increase of this magnitude in the rate of negative equity is estimated eventually to increase the possessions rate by 7 percent and the 6 month arrears rate by 3.5 percent. A ten percent increase in the unemployment rate from 8 percent to 8.8 percent is estimated to increase the possessions rate by 2 percent32 and the 6 month arrears rate by 10 percent. The sustainability of these relatively benign conditions is questionable, however, given the 31 In late 2009 the spread between mortgage rates on new loans and base rate was close to 350 basis points, with base rates at 0.5%. It seems likely that the spread would narrow with base rates at 1.5 or 2 %. Also with slightly higher base rates and hence higher deposit rates, retail saving flows into banks are likely to improve, perhaps easing credit constraints on lending. 32 This estimate is less accurate than the others and the figure could well be as high as 4 percent. 32 funding gap between retail deposits in UK banks and their loan book33, the time-table of withdrawal of the Special Liquidity Scheme and the Credit Guarantee Scheme, and concerns over the UK‟s sovereign debt.?, see Exploration of claimed link between Deposits and Bank Lending, in Werner Quantity Theory of Credit.???? ( otherwise this seems a very good paper!!! Two UK government objectives are to improve housing affordability and to restore financial stability. Housing has become unaffordable for many younger people, perpetuating the inequality from the redistribution of housing wealth of the late 1990s to 2007, from potential first-time buyers to older and wealthier households. However, substantial falls in house prices, triggered by the removal of income support, higher interest rates and potentially by supply and demand side reforms34 , could increase negative equity and exacerbate the problem of bad banking loans. It would, however, be a mistake to take the risk of substantial falls in house prices as an excuse for not expanding residential land supply. For if reforms of the planning system and of incentives for local governments to expand the supply of residential building land were to increase the rate of future building, DCLG‟s housing affordability model and research done for the Barker review suggests that the effects on house prices would be felt only gradually. A further advantage in the short-run would be employment gains in the building industry at a time when the public sector will be shedding jobs. In the long-run, a more sustainable level of house prices relative to the financial capabilities of households should reduce the risk of new crises.https://www.ftadviser.com/mortgages/2019/09/11/high-ltv-mortgages-spike-to-2008-level/

BoE data showed mortgages with LTVs higher than 90 per cent accounted for nearly 11 per cent of the market in the second quarter of 2007, but that had dropped to 2 per cent in the same quarter of 2009. Between 2009 and 2014, the share of high LTV mortgages spiked above 2 per cent in only three quarters but has gradually increased over the past five years.December 2020 The share of mortgages advanced in 2020 Q3 with loan to value (LTV) ratios exceeding 90% was 3.5%, 2.4pp lower than a year earlier (Chart 3). Back to December 2019, ( A year is a long time in Confidence Land.) Dan White, director at Champion Hall & White, thought the mortgage price war was partly responsible for the increase in high LTV products. He said: “Customers will opt for 90 and 95 per cent mortgages more partly because the rates have come down so much. “I think lenders are more willing to lend at the level, too, although it’s more strict than it was in 2007. A consumer’s affordability and credit score have to be strong to get a 95 per cent mortgage.” Mr White added that lending at 95 per cent LTV was acceptable as long as lenders looked after their borrowers and were willing to offer their customers new deals, rather than expensive retention rates. But Sarah Drakard, independent financial adviser at Cruze Financial Solutions, said the high share of high LTV mortgages was “worrying” because the property market was “just not strong enough” to deal with the risks. She added: “People forget about the financial crash. A few years ago, my first-time buyer clients didn’t want to buy a property with small deposits as they thought it wasn’t the ‘safe’ thing to do. “But now people are perhaps struggling to save, or parents are less willing to give money in unpredictable political times, so less people are able to save for big deposits.”    There’s more to house prices than interest rates BankUnderground Financial Stability, International Economics 03 June 2020 7 Minutes Lisa Panigrahi and Danny Walker There’s more to house prices than interest rates BankUnderground Financial Stability, International Economics 03 June 2020 7 Minutes Lisa Panigrahi and Danny Walker  https://bankunderground.co.uk/2020/06/03/theres-more-to-house-prices-than-interest-rates/ The average house in the UK is worth ten times what it was in 1980. Consumer prices are only three times higher. So house prices have more than trebled in real terms in just over a generation. In the 100 years leading up to 1980 they only doubled. Recent commentary on this blog and elsewhere argues that this unprecedented rise in house prices can be explained by one factor: lower interest rates. But this simple explanation might be too simple. In this blog post – which analyses the data available before Covid-19 hit the UK – we show that the interest rates story doesn’t seem to fit all of the facts. Other factors such as credit conditions or supply constraints could be important too. https://bankunderground.co.uk/2020/06/03/theres-more-to-house-prices-than-interest-rates/ The average house in the UK is worth ten times what it was in 1980. Consumer prices are only three times higher. So house prices have more than trebled in real terms in just over a generation. In the 100 years leading up to 1980 they only doubled. Recent commentary on this blog and elsewhere argues that this unprecedented rise in house prices can be explained by one factor: lower interest rates. But this simple explanation might be too simple. In this blog post – which analyses the data available before Covid-19 hit the UK – we show that the interest rates story doesn’t seem to fit all of the facts. Other factors such as credit conditions or supply constraints could be important too.  https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/uksectoraccounts/articles/nationalaccountsarticles/historicalestimatesoffinancialaccountsandbalancesheets https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/uksectoraccounts/articles/nationalaccountsarticles/historicalestimatesoffinancialaccountsandbalancesheets

1.Foreword Authors: Ryland Thomas (Bank of England) and Louisa Nolan (Office for National Statistics). The financial crisis has re-emphasised the importance of tracking the financial transactions of different agents in the economy and how those flows affect their balance sheet positions and the build up of risk in the financial sector. The current financial accounts published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) only start in 1987 although historical estimates based on earlier systems of national accounts are available back to the 1950s. This article outlines some preliminary work undertaken by the ONS and the Bank of England, with the encouragement and help of external academic consultants1, to try and reconstruct historical financial accounts and balance sheets by institutional sector for the UK. It sets out the challenges of reconciling accounts from a range of sources, which were produced with different methodologies and classifications, giving some key examples. In addition, several historical datasets for financial accounts and balance sheets, back to 1920, accompany this publication. 2.Introduction – the value of understanding the past The recent financial crisis has highlighted the importance of monitoring financial transactions between different institutional sectors in the economy and how financial assets and liabilities are distributed across different sectors on their balance sheets. Recently the ONS and the Bank of England published a review of the existing set of sector financial accounts, including some initial estimates of “from whom and to whom” transactions, using data already available in the compilation of the financial accounts. But, as recently highlighted by Bjork and Offer (2013), the analysis of financial transactions in the economy often needs to be put in historical context especially when financial crises are rare events. In particular, econometric-based policy work benefits from the availability of long time series that span different policy regimes and cover periods of structural change in the financial sector. The current set of published financial accounts and balance sheets began in 1987. Older estimates of the financial accounts are available back to the 1950s, following the recommendations of the Radcliffe Report (1959) and growing interest in modelling the financial interdependence between sectors Roe (1973). Measures of national and personal sector wealth are available for even earlier periods. The current post-1987 dataset roughly covers a 30-year period when the UK financial sector was largely liberalised and free of direct financial controls following various reforms in the 1970s and 1980s. But the recent introduction of macroprudential policy in the UK and the need to understand how its instruments work has rekindled interest in how the more controlled financial environment of the 1950s and 1960s worked. During this period the authorities operated various policies that, at least superficially, bear some resemblance to the tools at the disposal of today’s macroprudential policy makers. The Bank of England’s One Bank Research Agenda, suggests there are benefits from understanding the financial system of the 1950s and 1960s as it may shed light on how macroprudential tools might operate. Historical data on financial accounts and balance sheets is a key part of developing that understanding. Section 2 sets out the historical development of the financial accounts and balance sheets in the UK. In Section 3, the challenges of reconciling a range of historical data sources, produced using different methodologies and classifications are discussed. Section 4 looks at some examples in more detail, and conclusions are presented in the final section.https://bankunderground.co.uk/2020/06/03/theres-more-to-house-prices-than-interest-rates/  And here comes the No Shit Sherlock Moment! ' And here comes the No Shit Sherlock Moment! '

There could be a role for changes in credit conditions. The framework assumes that people are not credit constrained, meaning they can exploit arbitrage opportunities by buying up rental properties. If there are frictions in practice, this could mean that credit conditions matter for house prices. Mortgage debt expanded rapidly as house prices rose in the UK before the crisis, so this could be an important channel for the UK.Institutional real estate investors, leverage, andmacroprudential regulation Manuel A. Muñoz 14 November 2020 Institutional real estate investment has more than quadrupled in the euro area since 2013, financed largelythrough non-bank lending, which is not subject to regulatory loan-to-value limits. This column uses a two-sectormodel of institutional real estate investors calibrated to quarterly data from the euro area economy to showthat optimised (countercyclical) loan-to-value rules limiting the borrowing capacity of such investors are moreeffective in smoothing property price, credit, and business cycles than the well investigated dynamic loan-to-value rules that affect (indebted) households’ borrowing limit. The findings call for a strengthening of themacroprudential regulatory framework for non-banks.

BUILD TO RENT !!!!Utilising the Quantity Theory of Credit to Understand the Causes of the 2007 Financial Crisis Home » Educational resources » Sub-disciplines » Money, Banking & Finance © Copyright Maurice Starkey 2018 and available for reproduction under a Creative Commons CC-BY-SA license. Download this as a Microsoft Word document. Contents Introduction 1. Financial Deregulation 2. Credit money creation by banks and building societies 3. The Quantity Theory of Credit 4. Central Bank Policies to Manage the 2007 Financial Crisis 4.1 Should the Bank of England reduce interest rates in response to this type of financial crisis? 4.2 What type of quantitative easing is appropriate? Bibliography Footnotes https://www.economicsnetwork.ac.uk/archive/starkey_banking2

Banking crises tend to follow a period of rapid increases in asset prices (Reinhart & Rogoff, 2009). A substantial allocation of credit money creation for purchasing property and financial assets within secondary markets caused significant asset price inflation, which provided the context for the 2007 financial crisis (Werner R. A., 2013, p. 366). At some point the perception that assets may be over-valued influences investors’ perceptions of likely future price movements, and asset prices will fall when credit creation is no longer forthcoming for further asset purchases. This context produces a ‘Minsky Moment’ (Minsky, 1992). Falling asset prices cause speculators to lose money, and their loans will become non-performing because investors are unable to fulfil their contracted repayments. Banks have a relatively small capital cushion of around 10% of their asset base. Therefore, when the diminution in the value of a bank’s assets exceeds 10% it will cause the bank to become insolvent. Adair Turner (2017, p. 6) states: “The vast majority of bank lending in advanced economies does not support new business investment but instead funds either increased consumption, or the purchase of already existing assets, in particular real estate. Real estate is relatively fixed in supply, and consequently the transfer of funds to this sector leads to asset price increases that induce yet more credit demand and more credit supply, which is at the core of financial instability in modern economies”. The outstanding value of all residential mortgage loans was £1,527.3 billion at the end of 2020 Q3 two thirds of households own the house they live in; half of these are still paying off their mortgage 28,536,000 Dwellings 29,180,071,800 sq ft 29 Billion Sqft .

|

AuthorRoger Lewis, CEO of Home@ix writes this Blog, and the opinions expressed are his alone. Archives

July 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed